Most health and fitness writers don’t spend a lot of time on cartilage. It’s fairly isolated as far as tissues go. It doesn’t contain blood vessels, so we can’t deliver blood-borne nutrients to heal and grow it. Cartilage has no nerve cells, so we can’t “feel” what’s going on. Doctors usually consider it functionally inert, a passive lubricant for our joints. If it breaks down, they say, you’re out of luck.

But that’s the way people used to think about bone, body fat and other “structural” tissues: that they were inert, not metabolically active. The truth is that bone is incredibly plastic, responding to activity and nutrition, and body fat itself is an endocrine organ, secreting hormones that shape the way we metabolize. What about cartilage? Can we do anything to improve its strength and function?

Absolutely.

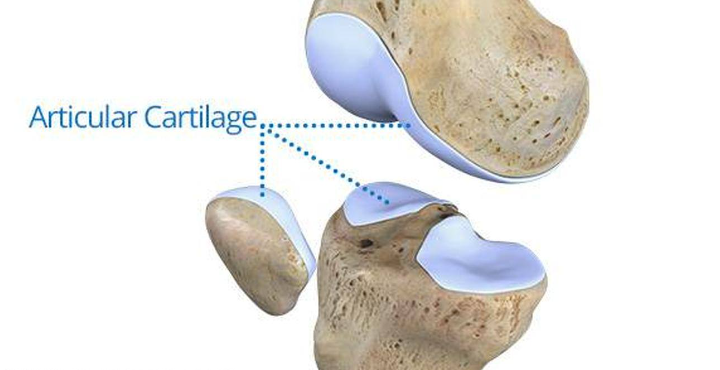

Cartilage is made up of water, collagen, and proteoglycan (a protein-polysaccharide bond that provides elasticity). Here we see one way to change the health of cartilage – hydration.

Stay hydrated.

Go to the pet store and look at those dehydrated tendons. They’re dry, hard, and completely unmanageable. Go to an Asian market and look at fresh beef tendons. They’re slippery, pliable, but still hard as nails. Now consider that cartilage and tendons are made of very similar substances. Without hydration, cartilage doesn’t slide easily. It can’t do its job.

Once cartilage is damaged, hydration becomes even more important because damaged cartilage is hard to hydrate. In one study, researchers dehydrated damaged pig cartilage and intact pig cartilage, then dehydrated them again, and found that the damaged cartilage absorbed far less water than the intact cartilage.

Eat more collagen/gelatin.

Our need for adequate dietary glycine and our collective failure to do so supports the growing bone broth/collagen supplement industry. The reason why drinking broth and eating collagen makes so many people feel better is because we are providing an essential nutrient:glycine. Our bodies need about 10 grams of glycine per day to maintain basic metabolic functions. We can only make 3 grams, so 7 grams must come from the diet. One of the main functions of glycine is to maintain and repair cartilage. If you are training hard or trying to recover from an existing injury, your glycine needs to spike.

Conclusive studies have shown that collagen to rebuild or support cartilage is lacking, but we have clues. One study found that collagen supplementation improved joint pain in athletes who complained of knee pain. More recently, a study found that taking dietary collagen and Tylenol improved joint pain and function in osteoarthritis patients compared to taking Tylenol alone.

My favorite ways to get collagen include bone broth, adding gelatin to pan sauces, and eating raw collagen bars.

Walk regularly.

Exercise is the lotion. You need to walk. You should get into the habit of exercising every day, even if it’s just doing bodyweight-related squats while brushing your teeth and waiting for the train, doing your favorite VitaMoves workout while watching TV, or an old-fashioned rajio taiso.

Be sure to include mobility work such as the aforementioned VitaMoves, KStarr’s MobilityWOD, or MDA’s writings on joint mobilization, foam rolling, and stretching. Many joint injuries occur because the tissues around them – your muscles, your fascia, your primary motion – are restricted, putting stress on the joints themselves.

Walking on all kinds of terrain.

Walking in civilization is not the same as strolling through a wilderness covered in rocks, low spots, fallen branches and slippery leaves, slopes, declines, and tilts. The former is linear and predictable. You just walk without thinking or reacting. It’s rote memorization.

Walking on different terrain exposes your cartilage to different positions and different loading patterns.

Barefoot.

It starts with the connection of the foot to the ground. If you block the millions of nerves in your feet from sensing the ground with a big thick piece of rubber, then everything in the kinetic chain is affected.

But do it gradually. After a lifetime of wearing protective footwear, going barefoot can be jarring. You don’t want to get hurt; being sedentary is terrible for cartilage (and other parts of the body).

Go back in time and quit the soccer team.

If you have kids, don’t force them to specialize. Participating in a variety of sports and activities early and waiting until late adolescence to specialize is better for future athleticism and safer for the joints. Let them be kids. Let them play, romp, and explore multiple sports. Or no sports, just sports, if that’s what they want.

The “chronic repetitive loading” of the joints associated with strenuous exercise can also lead to cartilage damage in adults. We can’t go back in time, but we can eliminate any chronic repetitive loading that the joints are still under.

Join an adult sports league, but don’t get addicted. Keep doing other things too.

Load.

Osteoblasts are to bone what chondrocytes are to cartilage. Just as osteoblasts respond to loading by increasing bone mineral density, chondrocytes respond to loading by increasing cartilage growth and repair. You have to load it or lose it. Studies on cows have found that cartilage is strongest in joints that are actually under load.

Studies have found that high-load, low-volume back extensions stimulate the healing of damaged discs (the cartilage that lines the spine).

Use a full range of motion in your lifts.

Full range of motion is the correct range of motion. This is what the cartilage is “meant” to process and respond to. For example, a deep squat is more likely to work the joint and make the knee more flexible than a half or quarter squat.

Of course, full range of motion is relative. If you can’t squat below parallel without moving forward, don’t force the issue.

Get out of the house and into nature.

Spending time in nature does a lot of good for your cartilage.

You’re more likely to be active, which allows your joints to carry the loads and multiple joint activities needed for health.

You get more sunlight, which is associated with better cartilage health in older people. Oddly, vitamin D supplementation has no effect, so it could be the sun.

You’ll lower cortisol and improve your immune response. Elevated cortisol has been shown to impede cartilage repair, and certain types of arthritis are inherently autoimmune.

Eat more omega-3 fatty acids and limit excess omega-6 fatty acids.

Eat wild-caught and fatty fish such as wild salmon or sardines. omega-3 has been shown to improve arthritis symptoms and even slow cartilage degeneration, and in rats, a balanced omega-3/omega-6 intake inhibits the expression of MMP13, a gene involved in the process of cartilage degeneration.

Don’t worry about nuts, avocados, or other natural foods that contain omega-6. Don’t get too crazy about them either. Be careful to avoid high polyfatty acid seed oils, which are the densest source of -6 in our diets.

Sleep.

Endogenous growth factors such as human growth hormone play a major role in cartilage repair. Without the help of medication, we take in the most growth hormone at night while we sleep. Whether we are recovering from micro-injuries caused by smart training and regular loading, or degenerative damage caused by poor mechanics and direct injury, sleep is where most of the repair occurs.

Maintain good sleep hygiene.

Find a slackline.

Read an article I wrote a couple years ago about slacklining. I still have the same one in my backyard and I still take frequent breaks to jump on it, keep my balance, and walk around.

Slip roping forces your body to constantly make tiny corrections. That’s why people who put their feet on a slackline for the first time will sway uncontrollably and feel like they don’t know their own bodies:They’re making huge demands on their neuromuscular system, demands that have never been met with such an unstable and dynamic environment. It takes them a while to find their bearings. The knees, hips and ankles have always faced very unique loading patterns.

Additionally, and this is not “science” or a quote, just personal instinct, anything that puts a smile on your face during training adaptations will be more effective than something that makes you make a face. Let your cartilage know that work is fun.

Lose the excess weight.

There may be too much load. We want the application of loading to be acute and intermittent. We want to control it. Therefore, exercise, hiking, jumping, squatting, climbing, running, and other short-term activities will often improve cartilage health, especially if proper technique is used and adequate recovery is allowed. But a 20–30 pounds weight gain is chronic loading because it never goes away. You can’t take that bag off.

Studies have shown that weight loss does improve cartilage health. In one study, obese patients with arthritis lost a significant amount of weight (5-10% of their body weight) and greatly reduced cartilage degeneration. For many of them, it stopped completely. If losing weight has this much effect on existing cartilage damage, imagine what it does to healthy cartilage.

These are the 13 most useful ways I’ve found to prevent cartilage damage and degeneration.

What have you found?